De-Palantirization

What comes next?

Palantir is having its NFT moment.

The mania has founders and investors alike researching and replicating the playbook that seems to be winning. a16z just penned an article about the “Palantirization of everything” describing how many startups are now attempting to be “Palantir for X” - build the picks and shovels, send in the forward deployed engineers (FDEs).

As an ex-Palantirian myself, I’m a long-time believer in the company’s mission. It deserves credit for being early and steady in pushing stodgy industries to adopt a software backbone not built internally or by a legacy vendor. It stood by working with the U.S. military, even when industry giants and even military leadership rejected them. It exports a nuanced but proven FDE culture.

Palantir now has a daunting task to grow into its valuation and double ~$4bn in annual revenue. And Palantir needs enterprise deals, not individual users. $10M deals start to look small at that level, and that creates an opening for every startup that sees $10M as a life-changing outcome.

The technological conditions that made Foundry dominant also are shifting (over the next 3-5 years, not tomorrow) toward products that may compete with Foundry, even on Foundry-shaped problems.

Enterprise software and integration are commoditizing

Software is becoming a simpler, more moldable expression of process knowledge.

It used to be harder to build software.

As a result, enterprise tech companies long focused on how to solve the maximum surface area of demand with the same product. One massive, horizontal platform to fit a broad space of problems. The sprawling microservices ecosystem. That strategy scaled both market size and margins. In the AI/autonomy world, this is Palantir Foundry for data-driven enterprise applications, Anduril’s Lattice for C2, Salesforce for CRM workflows, or Applied Intuition’s ADP for autonomous vehicle testing.

Historically, building something custom has been frowned upon in Engineering Land because of the long-term maintenance burden. I fought a few battles at Palantir to build custom product, then spent months getting it to a point where it delighted my target customer. Core product teams would push back: why not invest the time to build this generically so all future customers could benefit?

That tension was healthy and deliberately encouraged at Palantir. It’s how some of Foundry’s best products were born, and how other potential goose chases were avoided. But when someone like me stepped away, the custom code often entered a slow decline. Engineers would fret about the months of work to finally bury it. So the bias towards building “one platform for everyone” was very natural.

It used to be harder to integrate different software systems.

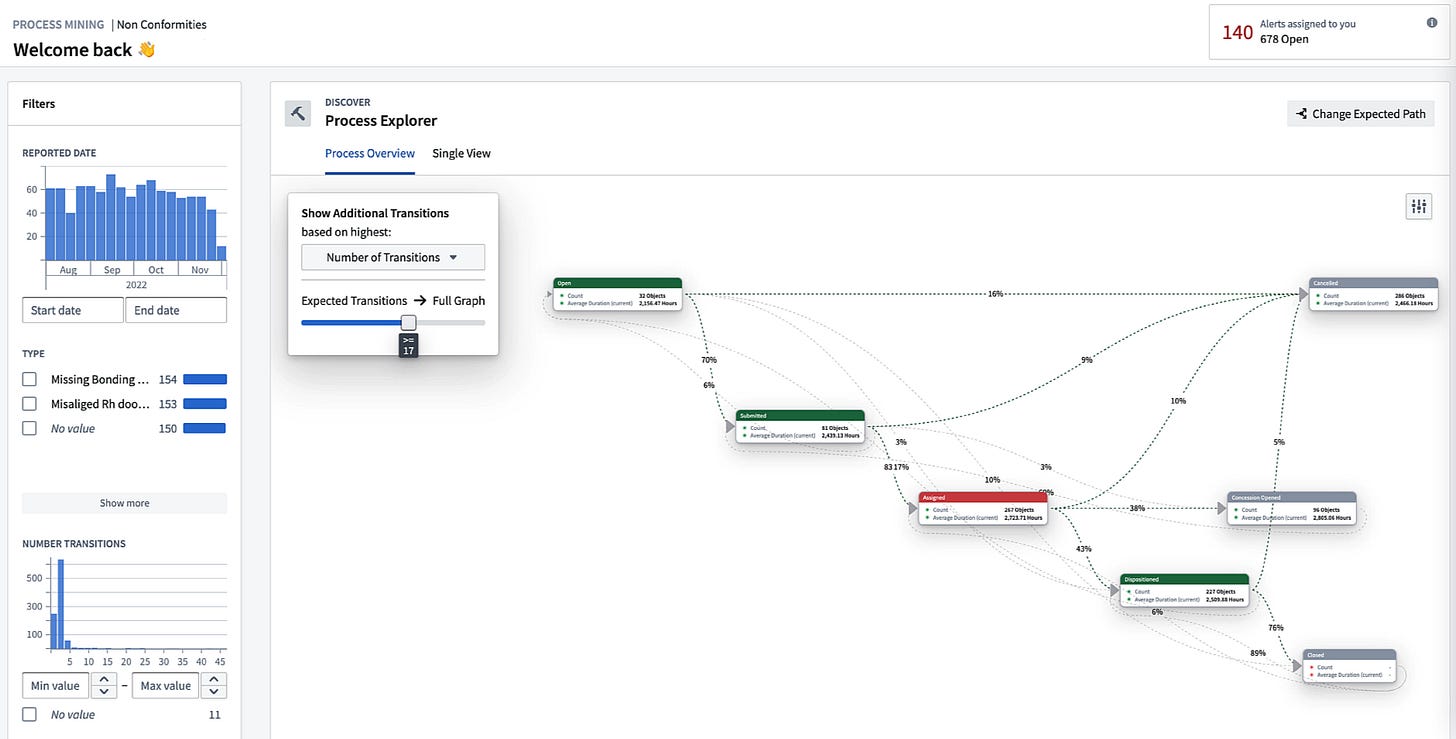

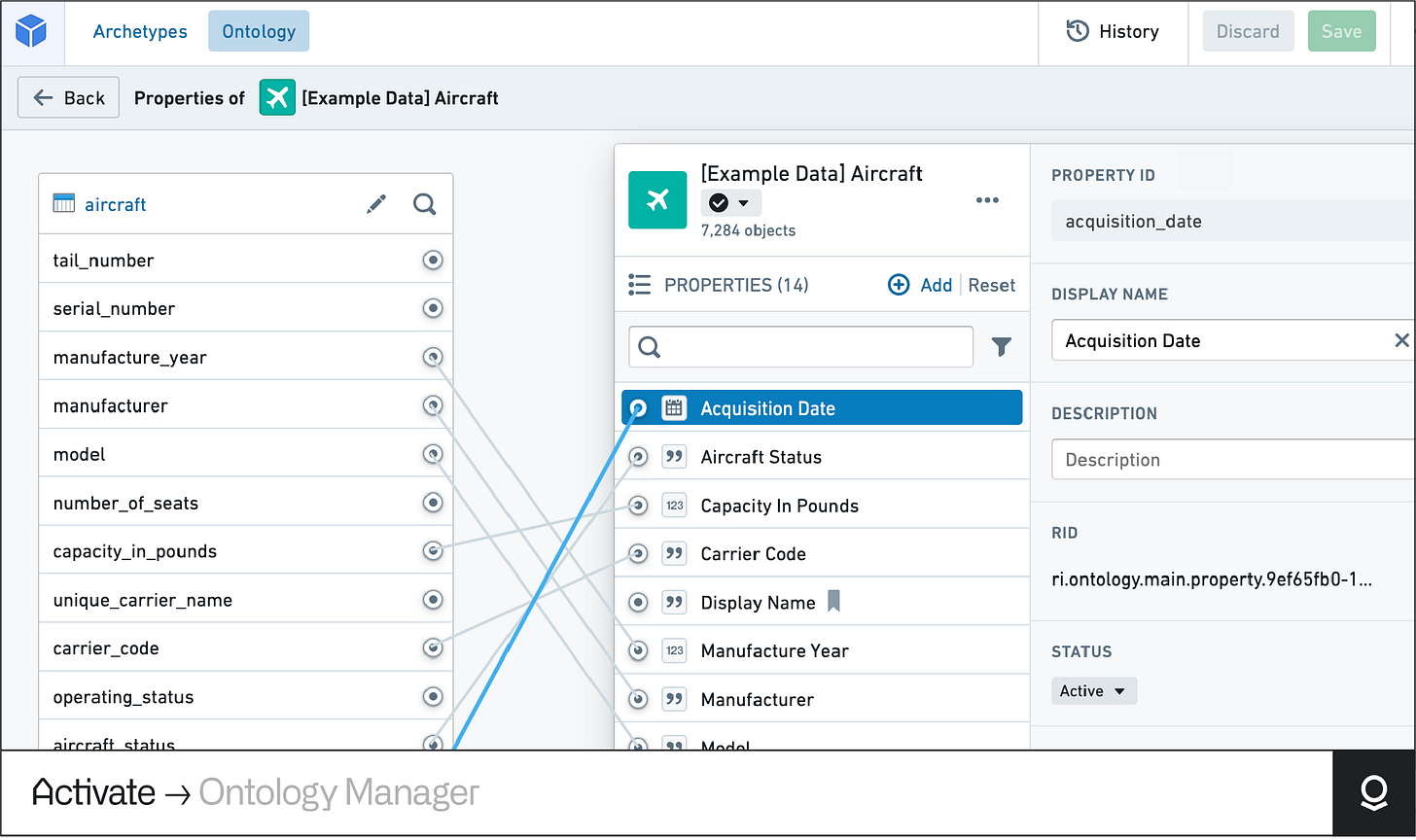

Integrating meant spending weeks writing and testing a new set of APIs, handing documentation to a third party, lots of meetings to align on those APIs, and then fixing some more bugs that surfaced while trying to integrate. As a result, enterprise technology companies tried to keep the data and workflow within their platform, or leverage the network effect. It’s easier to integrate with yourself! Other companies were seen as costly dependencies in engineering time to cooperate with. Forward deployed engineers (FDEs) like me became skilled first and foremost at integration tasks - implementing glue code, cleaning data with scripts, helping you write ontologies to model your world.

But 2026 is different.

It is getting much, much easier to build useful applications without manually writing a single line of code. Every employee is getting empowered to solve daily workflows with software they design themselves. The expectations for a product that just works for even niche use-cases are rising quickly. Companies will still want IT, security, and compliance centralized, but the application layer built on top of that could be scaled and professionalized by small teams when that used to take an army of developers.

It is also getting much easier to integrate different software systems. Companies are getting wise to that, using AI models to write documentation to be consumed by other AI models. If integration isn’t a headache, then having three best-of-breed tools stitched together might beat a single platform that is “okay” at everything. In some cases, this could challenge the Microsoft playbook of winning by bundling apps. If users deeply love a particular product, the willingness to manage the overhead of multi-app integration themselves (since this no longer handled by the app bundler) is dropping.

To be sure, you can’t yet replicate Foundry — the work of more than 1000 engineers over a decade — in 1000 Claude Code sessions. But you can replicate the narrow slice of Foundry’s functionality that you care about and optimize it to your needs.

The apprentice becomes the teacher

In the a16z post, Marc describes “highly opinionated” software platforms as a signature of Palantir. By “opinionated,” he means Palantir has strong opinions about how customers should define ontology, build data pipelines, and assemble applications.

But from the customer’s perspective, it’s the exact opposite: Foundry is uber-generic. It needs to be taught what “normal” looks like in their world through high-touch, expensive engagement with FDEs.

In 2026, customer expectations haven’t changed; they will just compromise less. Users always preferred a product that understood them out-of-the-box. It was just too expensive historically to justify building it.

For example, if I work in civil air traffic management, I’m not particularly delighted to see abstract “weather events” in my Foundry monitoring dashboard. It would certainly be better than the Booz Allen application from 2003! But my dream is to see METARs, TAFs, and SIGMETs expressed in the formats, terminology, and escalation patterns I already trust. I want the icons to look just like my FAA sectional charts.

Ontology is really just a schema, which is configuration. Foundry applications to build your applications are deeply generic. But we are unlocking the future we always (at least subconsciously) preferred of native, personalized product design. Unspoken defaults, walk-up intuitive workflows, a system that learns without you asking and sometimes even refuses a bad request. Horizontal platforms like Foundry that try to amortize UX across every vertical can’t fully commit to any one design language. So they have to bridge the gap with config.

That gap creates a lot of opportunities for “mini Palantir” teams across critical industries. Right now, there are many savvy engineers picking a domain, putting in the years to pick up expertise in it, and pushing those learnings into product. Over time, that tight loop outperforms broad platforms weighed down by competing workflows, system complexity, generic abstractions, and a diet of giant contracts.

Bridging to physical products

Palantir is a software company, and distinctly not a robotics company. Yet it is robotics, not software, that will most visibly transform the world in the next 25 years.

Software is the blood of robotics, it’s what gives life to hardware. But it’s going to get harder to make a dent in the biggest problems with just a SaaS product.

Robotics requires dealing with real-world phenomena. A robot cannot be developed, tested and deployed in a fully virtual loop. We have yet to design simulators that sufficiently approximate the infinite dimensions of reality and can be streamed with sufficiently low latency to act as substitutes for a real-world test (although neural simulators are maturing).

Only in the real world do we discover the “unknown unknowns”, the phenomena you’d never thought to code into your virtual model but can have disastrous consequences if your robot can’t handle them. I once had an autonomous trucking company tell me about a fish that jumped out of a lake and slammed into the windshield of its test truck while it crossed a low bridge. “Is that in your simulator?” the engineer smiled.

I’d predict the next era of giant companies will nearly all build hardware in a significant way. Even AI model companies like OpenAI. The defining organizations will be the ones to leave the comfort of abstract data models and wrestle with the messiness of reality.

Conclusion

Re-industrialization may be having its hype moment, but it isn’t a passing cycle. It’s a structural correction. Software spent a decade abstracting itself away from the physical world and now it’s being pulled back.

Palantir is undoubtedly a central chapter in that story. It is an extraordinary company with a lasting legacy, industry-defining products, and a generation of engineers trained to engage directly with consequential problems. Above all, it’s embedded itself into critical industries and won’t be dislodged easily.

But it’s precisely because Palantir proved the need for enterprise software operating systems that the next wave of innovators will go where Foundry can’t.

Watch closely for companies that preserve the mission focus and bottom-up learning but start to take ground in historically forgotten markets. They go for depth over breadth, and they will eschew the traditional one-platform model Foundry exemplifies. They will extend beyond software, even beyond hardware. That’s how you know “Palantir for X” is on to something.

Very excited for the wave of vertical software being built.

I'd argue that software also can't be built in a fully virtual loop. The biggest pitfall in software is assuming you understand how your customer will use your product. Technology (like AI) enables wildly faster iteration speed, but real-world usage + iteration is the only way to reliably make products that are actually valuable.

This essay really resonated with me on multiple levels, and you hit the nail on the head with watching “companies that preserve the mission focus and bottom-up learning but start to take ground in historically forgotten markets.”

I don’t know what the next 5 years will look like, but I’m excited to see what’s next for deep tech companies that take this approach, especially in robotics. It always an exciting time to build!